Popular Science asked us about Fire Starters

Whether building a fire outdoors or starting one in your wood oven or fireplace, a fire starter makes it easy to get a small flame…

1st November 2018

Extreme Low Tide foraging is becoming popular and one of the increasingly common requests we get for a private coastal foraging course over here in North Wales. It’s easy to understand why – when all of the most interesting and edible parts of the beach are under the water for part of every day then there’s a lot more to see when the water has retreated to its lowest point.

The UK is home to one of the biggest tidal ranges in the world – the Severn Estuary can have a difference of as much as 15m (49ft). The tidal range of one particular spot can be dependent on several factors, ranging from the shape of the bay, inlet or estuary where the range is being measured to the underwater geology and topography, and even the direction it is facing relative to the prevailing winds.

You don’t have to travel far to see a big difference between tidal ranges – the average tidal range in Colwyn Bay is about 8.5-9m whereas the range at Barmouth (only 42 miles away as the crow flies) is more like 4.5-5m. So a small building’s worth of difference in tidal range then!

When looking for wild edibles on the UK coastline the REALLY good stuff spends at least part of its life under the water – the edible seaweeds, molluscs, bivalves and gastropods and of course the fish and crustaceans. As the tide drops away (the ebb) then some of these species are left stranded on the rocks and the sand of the intertidal zone (the area between the high tide and low tide marks). This makes them easy to gather (as long as you’re doing it safely, legally and responsibly) and identify, and is also safer than wading around in deep rock pools and crashing waves!

For most of the UK the tidal period is around 12 hours and 25 minutes – the period between each high tide. The UK has what is known as a semi-diurnal regime – meaning that there are usually two high tides and two low tides every day. Other regions may only experience one tidal cycle in a 24hr period, such as happens in the Gulf of Mexico.

This semidiurnal regime gives the forager on the UK coastline two chances of reaching that intertidal zone on foot, although for a good part of the year only one of those chances is going to be in daylight hours!

Understanding the local tidal cycle is very important to anybody working or exploring that intertidal zone, whether it’s on land or in a boat. Fortunately – it has never been easier to access that information. There are multiple reliable websites, smartphone apps and other resources that help give reasonably accurate forecasts for the tidal cycle for any given location along the coast:

The published tide tables I use for North Wales and Anglesey are here and I often use a combination of these two websites for free online tidal predictions:

TideTimes.org.uk

Tide-Forecast.com

A strategy of using a combination of printed tide tables and online sources is probably wisest – I have the printed set in my truck and use it if I want to quickly plan a spontaneous trip to the shore.

For the UK specifically there is an excellent set of FAQs and diagrams on the National Tidal And Sea Level facility here.

I did consider doing our video on how tides work to help explain this point further – but then I discovered that BrainStuff had already produced on, at least a 1,000 times more interesting and concise than my ramblings would have been.

This video runs through how tides work, has a great visualisation of the ‘bulge’ of water created by the gravitational pull of the moon and a little more on the tidal cycle.

There are several factors affecting the cycle of tides on our planet, but the simplest way to think of it is to associate the tidal cycle with that of the moon in orbit around us. Imagine a ‘bulge’ of water being pulled out from the surface of the Earth towards the moon. As the earth rotates that ‘bulge’ of water can be seen by the fact that the sea ‘moves’ a little further up the shore. When the bulge disappears (i.e. moves away to another part of the Earth) it seems like the water level drops.

There are actually TWO ‘bulges’ of water, one directly under the moon and another on the opposite side of the Earth. This is where the rotational force of the moon and the Earth comes into play – the common centre of mass between the Earth and the moon isn’t in the centre of the Earth, but at a point a little clsoer to the moon.

This rotational force also has an effect on the ‘bulge’ of water, creating a second one on the opposite side from the one ‘under’ the moon.

As these two imaginary (but helpful for visualisation) ‘bulges’ pass by your area of coast then you will experience a cycle of the water rising, then receding as they come and go.

Yes, I know this isn’t particularly clear AND an oversimplification, but you reach a point with trying to understand tidal cycles where your knowledge of orbital physics and rotational geometry becomes more important than your knowledge of edible coastal species.

So for the coastal forager and hunter there are a few key things you need to understand and be aware of:

This is the term that has started to become popular for the point in the tidal cycle where the low tide is as far down the beach as it is likely to be. More properly it is known as a ‘Spring Tide’, and occurs twice per month.

Despite the name, Spring Tides have nothing to do with the season between Winter and Summer, but probably have something to do with the way the water seems to ‘leap up’ at high tide.

Maybe.

They do occur on regular cycle, usually a day or two after a full moon OR new moon.

If we go back to the simplified-but-helpful idea of there being two ‘bulges’ of water moving around the earth (‘under’ the moon and on the opposite side of the earth) then we can start to work out why Spring Tides occur.

The sun also has an effect on the mass of water on the surface of the earth, but much less than that of the moon. However – when the sun and the moon ‘line up’ relative to the earth then the effect of both of these bodies creates a bigger ‘pull’ than normally experienced. This happens twice per lunar month (which is approximately 29.5 days), and the noticeable effect on the Earth is that the ‘bulge’ of water is bigger/higher than at other times in that cycle. As the mass of water on the surface is largely unchanged then as more water is ‘pulled’ towards the Moon/Sun then the low tide in between the high tide will be as low as it can get – the water has gone away into the ‘bulge’ as it moved elsewhere.

This occurs a day or so AFTER a full moon or new moon, as it takes some time for the mass of water to ‘catch up’ with the gravitational forces.

Basically – when the sun and moon align there’s a bigger pull on the sea than normal, raising it slightly higher and further up the beach. Halfway between the ‘High Tides’ we get a the ‘Low Tide’, and during a Spring Tide the lowest point of the tidal range is as about as low as it can get – this, of course, is the really interesting part for the forager.

As there is a regular, predictable tidal cycle it is easy enough to predict when that extreme low tide event will occur. It will be roughly 6 hours BEFORE or AFTER the highest point of a Spring Tide, and local factors (shape of the coastline and underwater features) will affect which one of these two low tides will be the lowest.

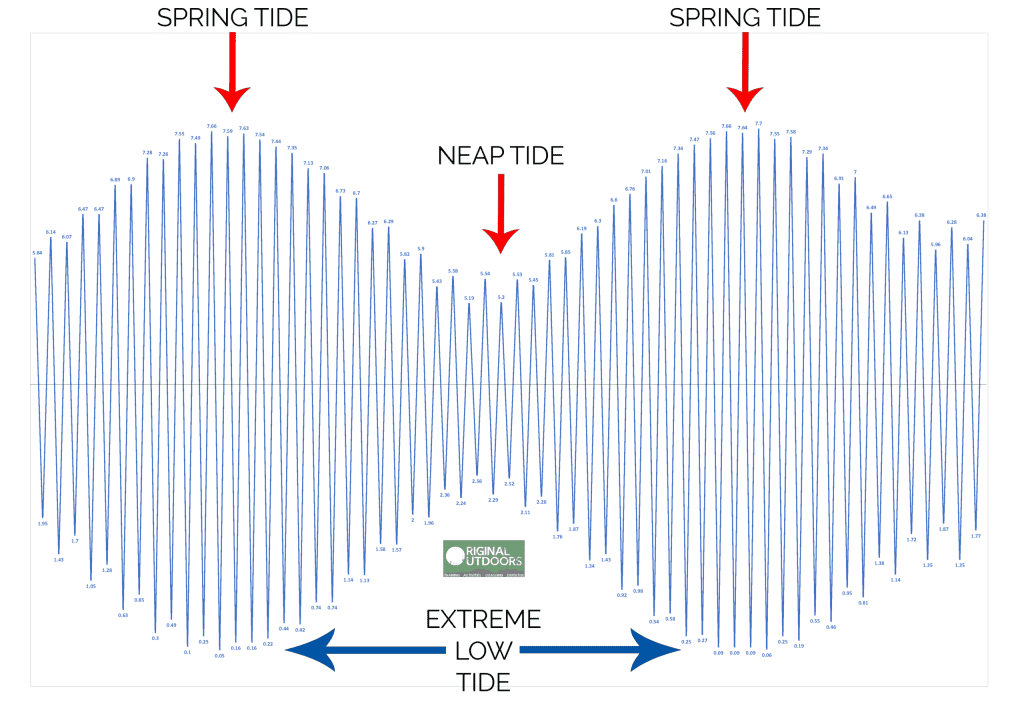

You can see it on tidal forecasting websites that show the next period of tidal cycles as a ‘wave’ diagram. You will see that the height difference between the ‘peaks’ of the wave and the ‘trough’ or ‘dip’ between those peaks changes from day to day. When the difference is greatest you are probably looking at the Spring Tide, and when the difference is at its least then you have the Neap Tide.

In printed tidal charts you can look to see the relative height of the high tide – normall listed in metres. When it is at its highest number then you are again probably looking at a Spring Tide. Some tidal charts will have a symbol or letter next to that Spring Tide, or have other information that help you calculate it for your area.

Neap Tides are simply the points halfway between the Spring Tides, when those lunar and solar forces cancel each other out. During a neap tide the high tide won’t be very high, but the low tide won’t be very low either. The tidal range for any location is at its lowest during a neap tide.

Within a lunar month (29.5 days-ish) you will usually find two Spring Tides and two Neap Tides. The cycle might look something like this:

Spring Tide > 7 Days > Neap Tide > 7 days > Spring Tide > 7 Days > Neap Tide > 7 Days > Spring Tide

So if you have just experienced a Spring Tide, with the extreme low tide that a forager is looking for, then you will have to wait roughly 14 days until the next one. This is of course dependant on several local factors AND the fact that the tidal cycle doesn’t exactly line up with a set of 24hr periods.

The above diagram shows the tidal cycle for roughly one month. Each ‘wave’ peak or trough on the chart represents one tide, with the ones under the line being low tide, and the ones above being the high tides. You can clearly see the two Spring Tides either side of a Neap Tide.

I keep mentioning ‘other factors’ that would affect how high (or low) any given tide might be, and it’s probably worth exploring that a little further.

The Wind

A strong wind blowing onto the shore can prevent the water from being able to move away as the tide recedes, and in narrow estuaries or coves this effect can be magnified. There is a term sometimes used – “wind over tide” – which refers to times when the wind and the tide are moving in opposite directions. This is particularly dangerous for anybody trying to broach the surf or head out to sea as the wavelength (gap between waves) is much shorter than normal and they can ‘stack up’ on each other. For the forager it can mean that the carefully-planned excursion to the beach to take advantage of the low water of a Spring Tide is scuppered by a strong onshore wind pushing the water further up the beach than expected.

Coastline Shape

Coves, narrow inlets and estuaries can trap water and hold it for longer than the area of coast either side if there is a narrowing or other restriction stopping the water from draining out as the tide recedes. This can be worsened by fresh water draining into a bay or estuary, ‘filling up’ the bay as the sea tries to drain away on a falling tide. Heavy rain somewhere inland combined with a Neap Tide can actually make for an almost negligible tidal range in some places along the North Wales coast – the water from the river fills up the estuary nearly as quickly as it drains away.

If for some reason you are incredibly impatient (or, more likely, you’re only on the coast for a short period and it doesn’t align with the Spring Tides) then there are a number of options open to you. However I must stress that buggering around in even very shallow water can kill you, or at least cause serious injury. Rocks are slippery below the high water mark, they can have hidden holes or openings that can trap legs (or cause you to slip and break something) and the mud of estuaries and shallow bays can entrap you or leave you stranded on a rapidly shrinking sandbar. It’s worth taking care and planning any in-water foraging very carefully.

It SOUNDS like I am being over cautious – but if you want to hear more have a word with your local RNLI or HM Coastguard teams and see if they thing the waters edge is a perfectly safe place to be…

If you want to make the very most out of any coastal foraging excursion then I strongly recommend just arriving during a falling (ebb) tide, at least 2-3hrs before low tide, and following the water as it receds. This way you find things that have only just been stranded by the receding water and more likely to be healthy and better for collecting.

A Mountain Leader with over a decade of experience across the UK and overseas, Richard is our Lead Instructor and a partner in Original Outdoors. He is a specialist in temperate wilderness skills and the wild foods of the British Isles, and also works as a consultant for various brands and organisations. Richard lives in North Wales.

A Life More Wild is the philosophy which underpins everything we do.

It encompasses practical skills, personal development, community learning and a journey to live more intentionally.

Whether building a fire outdoors or starting one in your wood oven or fireplace, a fire starter makes it easy to get a small flame…

In Tips From An Instructor we share useful snippets of knowledge to make outdoor skills that little bit easier. In this episode Richard explains why…

If you plan on transplanting snowdrops from one location into another, the best time of year to do this is as the leaves are fading…

Snowdrops are a beautiful, with their nodding white bell shaped flowers which secret away the intricately green lined centre underneath.