Popular Science asked us about Fire Starters

Whether building a fire outdoors or starting one in your wood oven or fireplace, a fire starter makes it easy to get a small flame…

3rd July 2017

If you have attended one of our courses or engaged me in conversation about the idea of survival training or prepping for potential survival situations then you will probably remember my having some fairly robust opinions on the whole subject. One of the points I often try to raise is that real survival situations – as opposed to heading out to ‘rough it’ with minimal gear – sneak up on you. You can’t see the situation building up in the distance, with a sweeping fanfare of your personal inner soundtrack heralding the arrival of your ‘moment’. The time when you get to put your training and preparation into action will probably just blindside you and throw you deep into a world of hurt – sometimes literally.

If you read up on real survival situations and those who have survived them (and more importantly, those who did not) then there is the common theme of being in denial about the whole situation. It isn’t just panic, although that plays a part – there is also an element of lethal familiarity.

If you spend extended periods in and around dangerous and life-threatening environments then the psychology of denial will help bury those risks and lead you to actions and behaviour that will betray you when the ‘bad thing’ actually happens. Inappropriate actions under threat can be anything from driving headlong into the raging river because it’s your regular route home and the water “can’t be THAT deep” to actively trying to push your rescuer underwater when your drowning reflexes kick in.

The way to combat these potentially lethal responses to danger is via two routes – awareness and training.

By being aware of your surroundings, the potential hazards and being realistic about how likely the various potential calamities are you can develop an appropriate response. Live in an area prone to earthquakes? You can read up on the current advice on what to do in case of a quake and what items you should have in your ‘earthquake survival kit’. Do you regularly travel in remote and wilderness areas? Then remote-area first aid training and equipment specific to wilderness first aid should be high on your list of priorities.

Television shows and gear manufacturers would have you believe that survival training is all about running up and down mountains, swimming in icey waters and knocking up a pile of useful equipment entirely from twigs and berries – but in nearly a decade of survival training with civilians, businesses, SAR, emergency services and the military the truth is a little less exciting.

Survival training can be split into two areas – prevention and reaction. Prevention is everything you do to make sure that you don’t end up in a survival situation, from ensuring your navigation skills are up to scratch to having a realistic approach to equipment and personal admin. Reaction is what you do in the seconds, hours and days following the ‘bad thing’ occurring. That kind of training is about building constructive automatic responses to life threatening situations and re-coding your brain so that your reflexes save your life and don’t kill you or endanger those around you.

Very recently a friend sent me an article she had written for somewhere else, and with her kind permission I have included it in this blog post. It perfectly illustrates all of the points raised above:

It was about midnight, -1ºC, nobody around, and I was due on an early shift the next morning. I’d spotted it was getting frosty so went out to the car to cover the windscreen so I could get away quicker in the morning.

I was wearing jeans with long boots underneath, a heavy fleece top, and was carrying my handbag.

As I returned to my boat, walking pretty briskly, my foot skidded on an icy metal panel and I fell flat with one arm – the one holding my bag – out in front of me. The weight of the bag and the fact that I was on a wet frosty wooden pontoon meant I just kept sliding. Strangely, I had two clear thoughts that I can still remember – 1) “I’ve fallen over”, closely followed by 2) “I’m under the water”.

Thankfully my keys were in my hand and I managed to fling them up onto the pontoon so that was one less thing to worry about.

It took a second for the feeling of cold to kick in, but sure enough, off went the gasping. I clearly owe a lot to my Wilderness First Aid training as we’d covered the gasp reflex and I knew in theory that it should stop soon – but now that I was actually in that situation did I risk waiting, or try to get out?? Because my clothes were so heavy with the water and there was no straightforward way out, I decided to test the theory. I held onto the pontoon, which thankfully I could just reach, and waited.

Sure enough, my breathing gradually came back under control.

Right then, I thought. NOW I’ll get out.

My first decision was that I needed 2 hands. Bye bye, handbag… Ideally I’d have got rid of my shoes but they were long leather boots which were under my jeans and it would have taken too long to struggle with them, so they stayed.

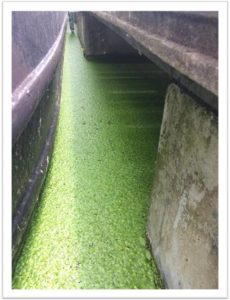

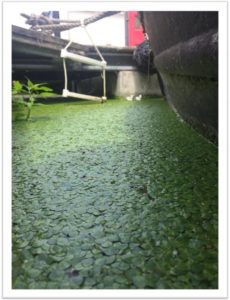

Even with both hands free it was far less easy than I’d anticipated. I was trapped in a small triangle of water between the bow of the boat and 2 pontoons at right angles to each other. The boat has smooth high sides, and the metal was frosty and there was no way I could climb up. I couldn’t touch the bottom of the canal – and frankly probably wouldn’t want to…

The pontoon was a floating one and when I tried to heave myself up onto it my legs just swung up underneath it, so I had nothing to push off. I tried that 3-4 times, and was aware I was getting very cold and tired and probably didn’t have the strength to try again if I failed again.

Over my head I could just reach the rope that moors the boat to the pontoon. I held onto it for a few seconds’ rest while I considered my options.

I could shout for help, but it was very late and I probably wouldn’t be heard, plus I was so cold I doubt I’d have got much noise out, yet I could end up out of breath or swallowing water. I decided this was last-resort Plan C.

I could go under the pontoon because I knew there was a ladder on the other side. However, having got my head above the water, I didn’t fancy going back under again. It was very dark and I didn’t want to risk being stuck under the pontoon or attempting to surface in the wrong place. That route became Plan B.

That left me with the option that did get me out – a gargantuan effort to flick my legs out of the water and cling sloth-like upside-down to the rope overhead. I managed to do that, and then to flip myself from there onto the pontoon.

Relief!! I made it!!

The relief didn’t last long, though. I was shivering violently, and realised I needed to get the wet clothes off fast. With numb and trembling fingers I managed to strip the heavy fleece off on the front deck, retrieve my keys (Yes!!) from where I’d managed to throw them earlier, get inside, and towel down and get a dressing gown on.

This being a boat, the indoor temperature was about 10ºC so I needed to get a fire lit in the stove, which took a little bit of doing in the chilled and weary state I was in.

As the room warmed up, I took stock. My arms, legs and ribs were bruised, battered and pretty sore from the various attempts to climb out.

I couldn’t phone anyone because my phone was in my back pocket, full of water, and useless.

I’d lost my purse and all my bank cards, driving licence etc, plus my work pass, as they were in the bag. I went back out with a net and fished for it, but no luck. In fact, despite the canal being only about 7’ deep and the bottom visible depending on the weather, and knowing precisely where I let it go, I’ve never found it – mystery!

I was about to head to bed when I heard a funny noise, like someone blowing a loud and prolonged raspberry. Just to add insult to injury, the ‘Key Buoy’ keyring I had attached to my keys suddenly activated, and shot out a huge flashing orange balloon which proceeded to mock me for the next 3 days. “Well, that’s a lot of use NOW!”, I shouted at it. I may have added some other words too.

I was on time for my early shift…

The RNLI is currently promoting a safety campaign that should be required reading for anybody who ever goes near water (so, pretty much everyone): Float to Live

A Mountain Leader with over a decade of experience across the UK and overseas, Richard is our Lead Instructor and a partner in Original Outdoors. He is a specialist in temperate wilderness skills and the wild foods of the British Isles, and also works as a consultant for various brands and organisations. Richard lives in North Wales.

A Life More Wild is the philosophy which underpins everything we do.

It encompasses practical skills, personal development, community learning and a journey to live more intentionally.

Whether building a fire outdoors or starting one in your wood oven or fireplace, a fire starter makes it easy to get a small flame…

In Tips From An Instructor we share useful snippets of knowledge to make outdoor skills that little bit easier. In this episode Richard explains why…

If you plan on transplanting snowdrops from one location into another, the best time of year to do this is as the leaves are fading…

Snowdrops are a beautiful, with their nodding white bell shaped flowers which secret away the intricately green lined centre underneath.